History of Himalayan Art

What comes to mind when we think of “Himalayan Art?” Statues of the Buddha? Striking paintings and intricate mandala designs? Images of angry-looking wrathful deities perhaps? Himalayan art encompasses all these forms and much more, typically intertwining the religious philosophies of Buddhism, Hinduism, and other tribal faiths with the indigenous cultures of Tibet, Nepal, northern India, and other areas under the cultural sway of these spiritual lands.

It was in the 5th century BC that Prince Siddhartha of India meditated upon the nature of suffering, achieved enlightenment, and became known as the Buddha, the Enlightened One. The Buddha then embarked on teaching his fellow Man how to move beyond the misery of existence by ridding themselves of desire and attachment.

As his following grew, devotees began constructing enormous sculptures depicting scenes from the Buddha’s life. Images of the Buddha and other enlightened beings became an increasing focus of art and devotion. Meanwhile, in Nepal and Tibet, artistic expression took the form of rock paintings and metalwork, depicting people, animals, scenes of herding, hunting, dancing, and religious activities related to the indigenous Tibetan Bon faith. Engraved metal bowls and teapots, prayer wheels, horns, and jewelry were made of bronze, brass, copper, or sometimes gold, silver, and iron.

Buddhist philosophies and iconographic art spread northwards to Nepal and Tibet by the 9th century, soon overwhelming the artistic traditions of Bon. Tibetan rock art dating back to the 11th century clearly suggests Buddhist influence with images of prayer flags, stupas, lotus flowers, and eventually, figures of the Buddha and bodhisattva. Gradually, artworks incorporated influences from Persia and China too. Nepal, particularly the Kathmandu Valley, was and is the artistic crossroads of Central Asia.

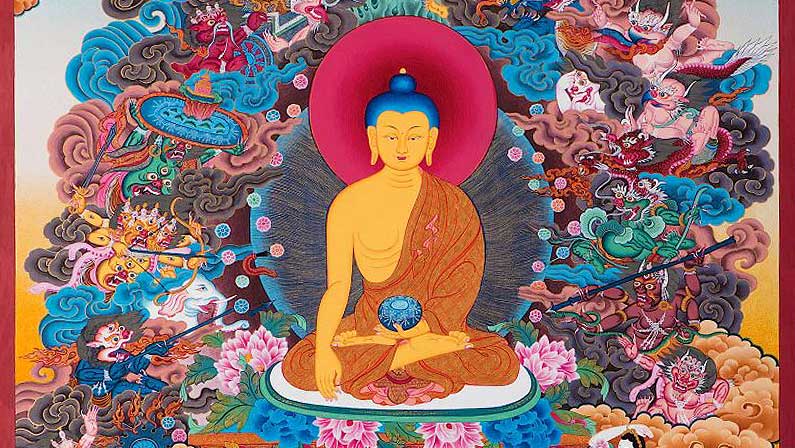

Prior to the mid-20th century, Himalayan art was dedicated to the depiction of religious symbols and philosophies, with the over-riding influence being Tibetan Buddhism. Monks and lamas commissioned thangka paintings for the teaching of spiritual messages; these scroll paintings were rolled up and taken across the country as teachers spread the word of the Buddha. Despite the existence of flourishing workshops, artists were largely anonymous as artistic creations were an act of piety, a sacred expression of the path to enlightenment.

In addition to thangka, other traditional Himalayan art forms include vast sets of paintings and sculptures. Several pieces are created as part of a much larger artwork with many individual components, such as a prayer altar or interior of a temple. Murals illustrating spiritual teachings, historical events, legends and the social life of Himalayan communities adorn temples and monasteries. Mandalas are a complex geometric design commonly used to help focus the mind and achieve a deeper meditation, an important aspect of spiritual practice, ultimately representing the universe and pathway to enlightenment.

Whether it be painting, sculpture, ritual objects, or architecture, Himalayan art is particularly recognizable through its complex iconography, composition, symbols, and motifs. Artists follow strict rules of iconography as specified in the Buddhist or Hindu scriptures regarding proportion, shape, color, stance, placement of hands, and attributes to ensure the correct personification of the Buddha and other deities. In fact, it can be incredibly difficult for curators to date some artworks as traditional artists have adhered to the same iconographic rules for centuries.

With its primary theme of spiritual growth, Himalayan art is renowned for its symbolism and storytelling. Many works contain lessons focusing on the importance of kindness, compassion, and generosity. The deities depicted do not exist as external entities but are emanations of a specific teaching. Their image in object form can, therefore, inspire spiritual practice and well-being, as well as beautify our environment.

Some deities are peaceful, others fearsome. The often angry-faced wrathful deities represent the Protectors, and their appearance belies their true nature. Wrathful expression represents their intense dedication to the protection of the dharma teachings. They also symbolize wrathful psychological energy that can be aimed at conquering negativity within the practitioner.

Today, authentic, handmade Himalayan art is being replaced increasingly by mass-produced factory products. Genuine antiques are rare. Many Tibetan Buddhist monasteries lost their collections through intentional destruction and lack of protection during China’s Cultural Revolution of 1966-76. While efforts are underway to restore the surviving monasteries and temples, more recent economic struggles throughout the Himalayan nations have contributed to the lack of authentic and one-of-a-kind works of art.

It is only through supporting local artists and collecting handcrafted Himalayan art, be it rare antiquity or contemporary design, that we can help to preserve the unique artistic and cultural heritage of the Himalayan region. In return, these deeply symbolic and spiritual artworks can inspire us all on the journey to enlightenment.